Les Misérables is an 1862 French epic historical fiction novel from Victor Hugo.

I was part of a book club last year. I joined the book club to talk to the people, yes. But mostly, I was interested in reading the book in question again. So when the club announced they were doing a new book starting in January, and the book would be Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, I was… skeptical. To say the least.

However, I figured I’d give it a try. I have a long commute, and listening to a 65-hour-book would definitely eat up my time. I’d always relatively enjoyed the musical, though all I’d seen was the 2015 version (which, I’m told, angers purists and theater fans. I don’t know enough about that, though). While I couldn’t sing any song from memory, the tunes of the songs definitely orbit through my head at weird times.

I’m currently through the first volume, out of five volumes. The whole book is around 650,000 words (about 2,500 pages, depending on the publication and translation, though all I have it the audiobook and a free PDF online). Each volume is split into books, and each book into chapters. I plan on reviewing each volume as we get to it in our monthly book club. While I know the broad strokes of the plot from the musical, I don’t know what differences came in adaption. I’ve been surprised so far.

I’m going to first give a broad plot summary, highlighting a few key scenes. After that, I’ll discuss the broader themes of the novel so far.

So far, I haven’t given any opinion on the work. Why is that? Is it because I hate it? Is it because I found this old, stuffy novel to be something of little particular interest for the modern person interested in storytelling?

Far from it.

Volume I: Fantine

Is it your soul that I buy from you; I withdraw it from black thoughts and the spirit of perdition, and I give it to God.

Bishop Myriel to Jean Valjean

The first volume stretches the span of time from 1796 to 1821. While the book starts in 1815 with the account of the Bishop of Digne and the arrival of Jean Valjean at his parish, it flashes back to the earlier episcopacy of Bishop Myriel and the youth of Jean Valjean. It ends with the death of Fantine as Jean Valjean begs Javert to let him return to rescue Fantine’s daughter, Corsette.

The first book starts with an absurd amount of information on the Bishop of Digne. Fourteen chapters—the whole first book—are devoted to the life and times of the Bishop of Digne, Bishop Myriel, or “Monseigneur Bienvenu.” However, two scenes make all of this description worth it. The first is in Chapter X, where Monseigneur Bienvenu confronts a dying homeless man on the edge of his village. The man was a member of the Convention, the philosophical heads of the 1789 French Revolution. The Revolution killed King Louis XVI of France, his wife Marie Antionette, as well as their young son, King Louis XVII, who died from neglect in 1793. The Convention member’s rationality and skepticism counter Myriel’s heavenly tranquility intermixed with royalist allegiance. Our view of Bishop Myriel is challenged. Overall, though, we see Bishop Myriel as a saintly person. He’s a piece of heaven on earth.

The second book describes the arrival of Jean Valjean in Digne. The second great event that makes Bishop Myriel’s time in the sun “worth it” is his release of Jean Valjean. A convict for 19 years, Jean Valjean has become a beast of a man, harboring a deep hatred for all society. With nothing to his name except a passport that forever assigns him the name “convict,” he stops at the house of the Bishop. The bishop treats him with profound dignity. In the night, desperate, haunted by his hatred for the society that wronged him, Jean Valjean steals the bishop’s silverware. Literal silver ware; the price of the silver spoons, knives, and forks would allow Jean Valjean to live again. It’s despicable, though, to take advantage of the kind bishop. He’s caught. He’s brought back to the bishop by the police. However, the bishop laughs, and tells Jean that he forgot the silver candlesticks as well. With this act of mercy, the bishop says, “Jean Valjean, my brother, you no longer belong to evil, but to good. Is it your soul that I buy from you; I withdraw it from black thoughts and the spirit of perdition, and I give it to God” (246). While Jean struggles with this redemption, he eventually decides to live for the good now that he is redeemed.

The third book flash forwards to 1817. It recounts the adventures of Fantine, a nineteen-year-old who left her family to enjoy the delights of Paris. She is in love with Tholomyes, a thirty-year-old man who thinks himself clever and must be in control of every conversation in every room. Her lover has three friends, and each of those friends has a lover. They are students at the university in Paris, living off of the riches of their parents while perpetually “learning.” In effect, though, they learn nothing at all. After two years and the height of romanticism, Tholomyes and the lovers abandon Fantine and her friends. Tholomyes leaves with a grand drunken speech, referencing Greek literature, rationalistic philosophy, and nihilism to show how love and commitment is meaningless. The ladies thinks he’s joking until the boys leave. The ladies laugh and move on to their next lovers, except Fantine. Fantine was in love; and Fantine is pregnant.

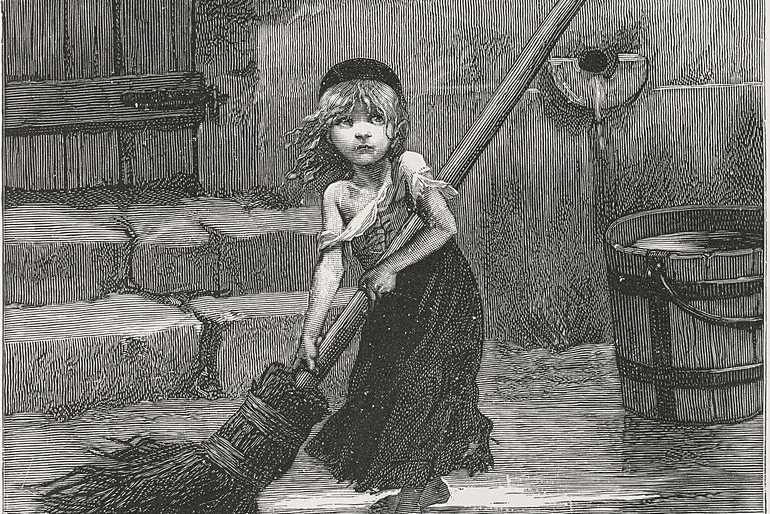

The fourth book tells of how Fantine, now with a child several months old, attempts to return to her hometown Montreul-sur-Mer to find work. On the way, she stops at an inn. She leaves her child with the innkeepers, knowing her town will ostracize her if she brings a child out of wedlock. The innkeepers turn out to be dishonest, abusing little Corsette and demanding progressively more money from Fantine at her factory job back in her home.

In less than three years he had become rich, which is good, and had made every one about him rich, which is better.

About Monseigneur Madeleine

Book five is the center of this volume. It first flashes back to the founding of this factory. In Montreul-sur-Mer, in 1815, a poor wanderer by the name of Madeleine discovers a way to improve their jewelry business. In one fell swoop, the town goes from a backwater to thriving town of commerce. Madeleine is extraordinarily generous, thoughtful, and kind. “In less than three years the inventor of this process had become rich, which is good, and had made every one about him rich, which is better” (340). He becomes the mayor. His only detractor is Javert, chief inspector of police in the town. He is a man of justice, following the law to the letter and never detracting from it. He distrusts Madeleine’s rise to power and kindness, believing it weakens the law and the status of the gentry of the city.

Book five continues Fantine’s story as well. In 1518 Fantine begins working at the factory. However, gossip gets out that Fantine has an illegitimate child; the woman who is the head of the female jewelry makers fires her. As Fantine’s debts rise, she sinks into the depths. The depths of hatred for Madeleine, who she is convinced fired her. The depths of poverty, selling her thick hair to a barber, her two front teeth to a traveling medicine man, and her body in prostitution. She’s finally arrested by Javert. In another key scene I’ll discuss later, Madeleine intervenes and lets Fantine go, for the sake of her child Corsette. Fantine falls ill, and Madeleine attempts every day to bring Corsette home. The innkeepers won’t budge.

In book six, Javert, blinded with rage, sends a report to the chief inspector of police in Paris. He believes Mayor Madeleine to be none other than Jean Valjean in disguise. Javert was one of the masters of Valjean’s chain gang while he was imprisoned and held suspicions about Madeleine’s identity for years. However, he comes to the mayor, chastised, and demands to be sacked. Why? The mayor asks. Because he made a false accusation: Jean Valjean was caught and will be on trial soon.

Should he remain in paradise and become a demon? Should he return to hell and become an angel?

Jean Valjean’s Inner Monologue

The seventh book is the most moving of the volume. For Javert was right. Madeleine is Jean Valjean. The man on trial is not Valjean, but an innocent man mistaken for him. Jean Valjean has spent the last six years of his life giving it back to God, living out the redemption the priest won for him with those two silver candlesticks and knapsack full of silverware. In one of the longest chapters in the whole novel, Jean stays up all night debating his next action. He cannot let an innocent man die. But he has done so much good for this town. Yet to send that man to the abyss makes him a coward. And yet he has a promise to keep to Fantine. What shall he do? ” ‘Should he remain in paradise and become a demon? Should he return to hell and become an angel?’ What was to be done? Great God! what was to be done?” (480). Jean Valjean races to attend the trial of the man, unsure what to do… until he sees the poor man embarrassed by the lawyers and audience during the trial. Jean Valjean declares his identity and provides unquestionable proof. Leaving the courtroom in shock, he heads back to Montreul-sur-Mer.

In the final book, book eight, Fantine is between death and life. She has convinced herself that the Mayor Madeleine left in order to return with Corsette. Yet when Jean Valjean returns, without Corsette, and then Javert hurries in to arrest Jean Valjean, Fantine dies of shock. Javert is cold and ruthless. Fantine, a whore, deserves to die the way she did; Jean Valjean is an ex convict. Javert has all the joy of someone proven right after facing intense shame. Valjean goes to prison willingly after mourning Fantine. However, he escapes in the night and makes his way to redeem his mistakes with Fantine. He will rescue Corsette, no matter the cost.

Here ends Volume I of the novel. I’ll review the other volumes as they come up in my book club, but for now, let’s look at the major themes of this volume so far.

Themes

The two major themes of the novel in Volume I are the unconstrained vision and law versus redemption. Both of those are interwoven throughout the entire first volume as we’ve seen.

The Unconstrained Vision

The Unconstrained Vision is a political philosophy in contrast to the Constrained Vision. They are two philosophies that are in tension over the nature of… well, human nature. The terms were coined by the political and economic philosopher Thomas Sowell. (Sidenote: this former Harvard professor is 92 years old… and still writing and publishing books. Wow.)

The Unconstrained Vision is the view that people are naturally good, and that society is what ruins, corrupts, and makes them fall. Therefore, society must be reformed: culture must be realigned. Better policies will unencumber people to be the good people they are meant to be. Welfare and charity will necessarily give the resources to people to unlock the goodness inside of them, since their circumstances are what necessarily lead them to being evil. So, the goal is the reformation of political and social institutions in order to return people to the way they are supposed to be. In modern culture, that would define the “left,” but that has not necessarily always been so.

The Constrained Vision is the view that people are naturally evil, and that society and culture are curbs that keep people’s worst impulses in line. Therefore, society must be preserved; culture is the bulwark that keeps our people from falling apart. Better policies are of course possible, but the policies themselves necessarily are punitive and attempt to reward the right and condemn the wrong. Evil is ready to break out at a moment’s notice, so we must remain vigilant. In modern culture, this would define the “right” overall, but again that has not always been true either.

For an example of “reversal” of constrained and unconstrained, at the time of the Reformation of the Western Church, the “left” was constrained and the “right” was unconstrained (depending on how you view left and right). The Reformers claimed they were returning to the original doctrine of the Christian Bible, which advocates a Constrained Vision; however, they were reformers and could be viewed as “left”. However, the Catholic Church had developed a doctrine of Unconstrained Vision, that every person has a divine spark given by God that knows good and can choose it. This development heavily influenced the later development of Western and European morality.

Victor Hugo is clearly a proponent of the Unconstrained Vision. In prison, Jean Valjean ponders his unjust treatment—after all, he was punished just for stealing a loaf of bread to feed his sister’s children. “Jean Valjean had not, as we have seen, an evil nature. He was still good when he arrived at the galleys. He there condemned society, and felt he was becoming wicked” (215), In his thoughts, he concludes: “He judged society and condemned it. He condemned it to his hatred” (213).

Victor Hugo will break in occasionally to offer his musing on human nature. He adds to Valjean’s judgments, “Does human nature thus change utterly and from top to bottom? Can the man created good by God be rendered wicked by man? Can the soul be completely made over by fate, and become evil, fate being evil? … Is there not in every human soul, was there not in the soul of Jean Valjean in particular, a first spark, a divine element, incorruptible in this world, immortal in the other, which good can develop, fan, ignite, and make to glow with splendor, and which evil can never wholly extinguish?” (215). Hugo’s comments that he adds concerning the mistreatment of Fantine in her poverty as well as comments about poverty he makes along the way show that he believes institutional change would change poverty.

The assumptions he bases his characters on show his unconstrained vision. People are good; the actions of others make them evil in response. Jean Valjean stole a loaf of bread because his family was starving. Fantine does evil because she needs to provide for Corsette. Fantine won’t send for Corsette because she’s afraid that child will have to live with her evil choices. Even the member of the member of the Convention did what he did for good reasons. He wanted society to improve. He wanted a better tomorrow; for no more children to die. To be as outraged over the death of the poor as the death of a prince.

Victor Hugo thinks humankind is naturally good, while the actions and institutions of society make them evil. However, what is more important than his view on the nature of evil is his view on what to do with those who do evil. What then? Now that they’ve done wrong, how should we as society or we as individuals react?

Law versus Redemption

So many characters in Les Misérables face the full brunt of law and justice. However, so many also receive wonderful redemption. Once, when those two meet, we see the conflict nature of law and redemption. But first, how does Victor Hugo see law?

To Jean Valjean, justice is to be feared. “Besides, human society had done him nothing but harm; he had never seen anything of it save that angry face which it calls Justice, and which it shows to those whom it strikes. Men had only touched him to bruise him” (214). We see that justice is necessary. Valjean knows he did wrong; he acknowledges it. However, he then decides that society did wrong in punishing him as they did, turning him angry and bitter. Justice doesn’t change minds; it only embitters them.

Fantine deserves her punishment, she thinks; however, that does not keep her from being bitter toward justice. When she is brought before Javert for insulting a gentleman of rank who bullied her, she knows punishment is just for her (406). However, her initial fall comes from, she thinks, Madeleine. “By dint of repeating to herself that it was he who had discharged her, that he was the cause of her unhappiness, she came to hate him also, and most of all” (383). Perhaps his response was just, in his mind; but that does not mean she needs to love justice. Again, law embitters but does not change.

Javert is the personification of justice. Humorless, cold, inhumane. When he condemns Fantine to prison, he thinks as much: “The policeman should become a dispenser of justice, and that, in this prodigious extremity, order, law, morality, government, society in its entirety, was personified in him, Javert” (408). Fantine begs for him to release her for her crime, for the sake of her daughter. But law, order, and government show no pity. It is not their job. It is the job of justice to convict. That is God’s duty, in Javert’s eyes. “Come! I have heard you out. have you entirely finished? You will get six months [in prison]. Now march! The Eternal Father in person could do nothing more” (402). The Eternal Father couldn’t betray his nature to be just. To Javert, justice is the unpitying height.

Justice reaches its height in the courtroom where Jean Valjean’s doppelganer is put on trial. Victor Hugo describes the courtroom; this courtroom is Law: the details show that, “from all this there was disengaged an austere and august impression, for one there felt that grand human thing which is called the law, and that grand divine thing which is called justice” (540). Then what does justice do? It belittles, mocks, and condemns an innocent man. Justice undermines its very nature. Victor Hugo shows how he views law. Order is good; even Javert has his sympathetic and human moments.

However, in the battle between law and redemption, justice and pity, it is grace that wins. Only grace effects true change. Only redemption will cause true change.

There are a handful of moments of key grace in Les Misérables. One is Fantine’s redemption from jail in book five. Jean Valjean, in disguise as Mayor Madelein, and Javert battle for the soul of Fantine. Javert will not yield; the Law must stand. But Jean Valjean is pity, and mercy, and grace, and redemption. Fantine sees this: “She had just seen herself a subject of dispute between two opposing powers. She had seen two men who held in their hands her liberty, her life, her soul, her child, in combat before her very eyes; one of these men was drawing her towards darkness, the other was leading her back towards the light. In this conflict, viewed through the exaggerations of terror, these two men had appeared to her like two giants; the one spoke like her demon, the other like her good angel. The angel had conquered the demon, and, strange to say, that which made her shudder from head to foot was the fact that this angel, this liberator, was the very man whom she abhorred” (412). Grace wins over law. Grace actually changes a person. The rules and structures of society, no matter how much they attempt at justice, will never reach the glory of an individual soul encountering an individual soul. This brings nuance to Victor Hugo’s view of the unconstrained vision. While yes, institutional change is good, mercy will triumph over justice.

The greatest and most well-known redemption is Jean Valjean’s. We’ve already discussed it previously, so we won’t get into it again. But the candlesticks given to Jean Valjean by the Bishop of Digne changes the trajectory of his life. He goes from a man angry at society, to a man who will give his entire life to save a single innocent man.

But we know what Victor Hugo thinks. In the mouth of his messianic character, the Bishop of Digne, we hear the truth: “The judge speaks in the name of justice; the priest speaks in the name of pity, which is nothing but a more lofty justice” (125).

Redemption, grace offered to those who do not deserve it any longer, is the height of virtue. It is God himself, it is Christ himself, who cares for those who no one cares for. Redemption is higher than law in the world of Les Misérables.

Les Misérables was written by Victor Hugo. It was originally published in 1862, and is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century. I listened to the Audible version of the Penguin Classics 1982 translation. The PDF I quote from is the Free Classice Books version.

𝙷𝚒! 𝙼𝚢 𝚗𝚊𝚖𝚎 𝚒𝚜 𝙽𝚊𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚗. 𝙸’𝚖 𝚊 𝚐𝚛𝚊𝚍𝚞𝚊𝚝𝚎 𝚜𝚝𝚞𝚍𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝚠𝚑𝚘 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢𝚝𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚕𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚛𝚎𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚘 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚝𝚊𝚕𝚔 𝚊𝚋𝚘𝚞𝚝 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚖 (𝚜𝚘𝚖𝚎 𝚠𝚘𝚞𝚕𝚍 𝚜𝚊𝚢 𝚝𝚘𝚘 𝚖𝚞𝚌𝚑!) 𝙵𝚘𝚕𝚕𝚘𝚠 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚋𝚕𝚘𝚐 𝚝𝚘 𝚜𝚎𝚎 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚎𝚗𝚝!

Leave a comment