Guns, Germs, and Steel is a 1997 Pulitzer Prize winning historical review by Jared Diamond, proposing a “theory of human interaction” that provides unifying rationale as to why certain societies or ethnicities conquered others. The 20th Anniversary Edition expands on some chapters and adds a new afterword.

This is a difficult book to read, for three reasons.

First, do you like nonfiction? I do. But if you don’t, this will be hard to read. It’s informational; while Jared Diamond tells stories of his experience with tribal peoples of New Guinea, relating them to his theories, it’s still largely information. Loads and loads of information.

Second, the content of the loads and loads of information. This is a transdisciplinary work, covering evolutionary biology of plants and animals, linguistics, genetics, geography, thousands of years of political history, categories of societies; so, so much is covered in these pages. Keeping track of the rationale for his conclusions is hard because he’s summarizing so much data.

Third, the content is hard.

Why did Europeans conquer Native Americans, and not vice versa? Why didn’t Africans pick apart Europe, reaping its spoils? Is there a way to quantify these reasons that don’t involve racial or ethnic hierarchy, that is, people of African heritage are just less smart than people of European heritage simply due to genetics?

Jared Diamond attempts to find an overarching theory of human-environmental interaction that is testable and repeatable. He spends his final chapter (before the 20th Anniversary Edition Afterword) outlining his theory as History As Science. While it is not physics, history is still a science. You gather information, then make theories, and then see if other data matches the theories and framework you have created.

So, what is Jared Diamond’s theory? Is this book worth the 400 pages and the months I’ve taken to read it?

A Summary

There are four main parts to this book, as well as a prologue and epilogue.

The prologue sets the stage. Jared Diamond worked studying rare birds in New Guinea in the 1970s. He spent intensive time among the local people of the island of New Guinea. During that time Yali, an advocate for the local people of Papua-New Guinea before it was an independent country, asked Jared Diamond a question.

“Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little cargo of our own?”

By “cargo,” Yali meant anything the whites brought to New Guinea: centralized government, steel axes, medicine, umbrellas–things the native New Guineas instantly recognized as a whole as valuable.

So why? Why the Europeans, the white, to Asia and Africa and the Americas and Australia? Why?

Part one is called, “From Eden to Cajamarca.” It’s a summary of the history that underpins this books. First, it describes the development of continents and people traveling across those continents until 11,000 BC, by common consensus of evolutionary theory. Then, it breaks down the geographic and societal uniqueness of the Polynesian islands. Finally it describes the situation within Incan and Spanish societies when they impact in the 1500s. This section is descriptive. It lays down the situations, the situations that many people know but don’t know in detail. We see the conundrum in full. How do we explain the end result of how these societies developed, and where they were when they impacted?

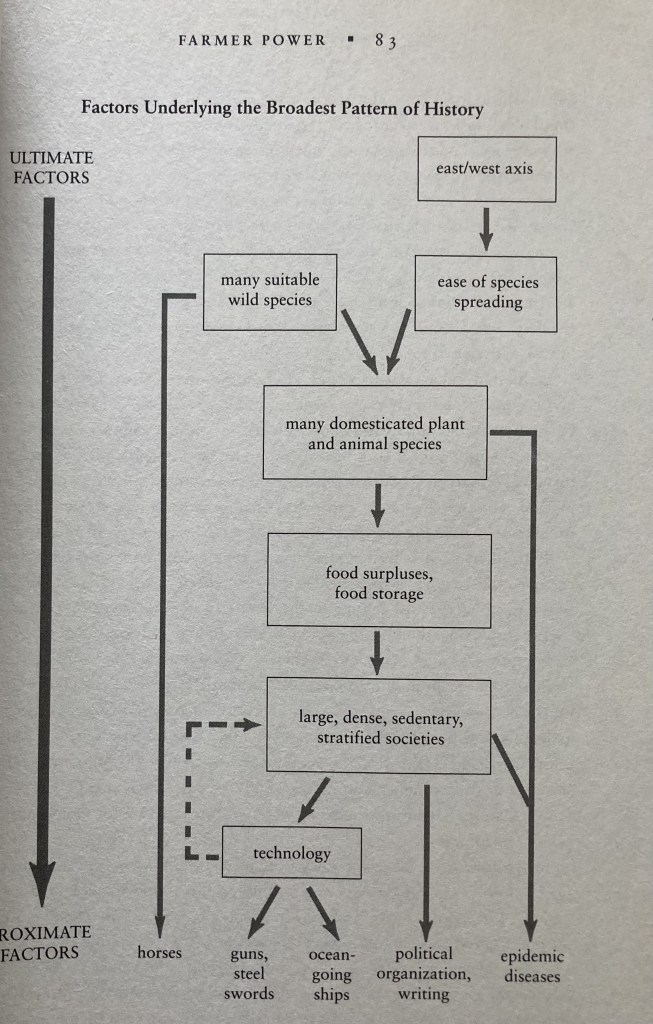

Part two is titled, “The Rise and Spread of Food Production.” These are the scientific chapters. They are summarized by the simple chart I’ve included below, from page 83 of the Twentieth Anniversary Edition. The cut-off word is supposed to be “Proximate” factors.

This part seeks to explain each section on that chart. First, that the east/west axis of the Eurasian landmass (Europe and Asia and northern Africa) made it much easier for domesticated plants and animals to be adopted by different societies across the continent. Meanwhile, in north/south axis landmasses (Africa and the Americas), plants or animals domesticated in one area had difficulty spreading further north or south. Think of an orange; it can be grown in lots of the same climates across the world, but it can’t travel from Florida to Wisconsin. Meanwhile, grain that grows in Wisconsin grows across the entire Midwest and around the world at that same longitude, in Germany, Ukraine, northern China.

Along with that, the truth is, the Fertile Crescent and China contained lots of native species of both plants and animals that could be domesticated; the Americas and Africa do not, even until this day. Pigs came from China and the Fertile Crescent; pig-like Javelinas in Arizona, however, have not been domesticated. Increase in food supplies leads to settled societies, which leads to denser societies, which increase the probability of inventions finding use, and so on. The chain of cause and effect is large and long. A grain that was more likely to develop a mutated gene near the Euphrates eventually led to Columbus making landfall in the Caribbean.

Part three is titled, “From Food to Guns, Germs, and Steel.” It deals with the final links in that chain, such as germs and disease, writing, technology, government, and religion. Jared Diamond makes the point over and over again; no group of people is necessarily smarter than any other group of people. Europeans are not smarter than New Guineans. Though we can find differences between individuals, humans as a whole are creative, problem-solving people, willing to adapt to the new they see in order to overcome the challenges they face. Some groups possess traits other groups do not possess, such as tending toward conservatism or change. However, looking at humans as a whole, we see a trend. A trend toward adaption.

An illustration is helpful here. Toward the end of the book, Jared Diamond provides an example: Looking a hospital, he could tell anyone that per 1000 babies born at that hospital, no less than 480 and no more than 520 will be male. However, that doesn’t help him predict whether or not his child will be a boy or a girl. We find trends; we study the patterns; we see the science. That won’t help us in each individual case; but we can still see the patterns writ large.

This is when part four comes in to put his theory into practice. “Around the World in Six Chapters” gives an overview of six major people groups and how they conquered. Jared Diamond can’t tell you whether the United States of America will last another hundred years or collapse in the next ten. However, he can show you how the colonization of North America by White Europeans fits the trend of societies throughout history. “Black” Africans (a misnomer, as Diamond spends several pages criticizing using that name but then uses it for lack of a better term) from south of the Saharan desert conquered. They pushed “pygmies” and Khoisan further and further south of Africa to the point of near extinction when they obtained and developed on agriculture they had received from the Near East. Ethnic Chinese conquered Austroasiatic people out of southern China and southeast Asia. These societies around the Yellow River and Yangtze River developed or borrowed agriculture and then eventually settled societies with superior numbers, let alone more deadly weapons and more efficient inventions.

Over and over again, settled societies grew, spread, and eventually conquered. Humans as a whole are inventive and adaptive. Human groups that settle tend to grow, and then conflict with those they come into contact with. Those that have what is traditionally called “civilization” usually win; but they don’t have that “civilization” because they’re superior in it of themselves. They have it because their geography and access to other societies gave them different tools.

The epilogue then brings the comparisons out of about 1500. The six chapters stopped at the edge of the “modern era.” In the epilogue and afterward, Jared Diamond brings his conclusions into a more modern context. In 1300, no one would have guessed the societies of Europe would have conquered much of the globe. China was hundreds of years of development and millions of population ahead of Europe. The Muslim empires of India, North Africa, the Middle East, and Indonesia had much of the “civilization” in the form of writing, agriculture, and population.

Yet in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. That genius-level navigator and crazy millennialist honor-bound Reddit conspiracy theorist sailed. Why? Because Europe’s many ports and few large rivers created many small competing societies, rather than a larger mostly homogenous society, such as China. When the Fertile Crescent’s ecosystem was eventually stripped bare, Europe’s tougher ecosystem more used to bouncing back kept supporting larger and larger societies. Eventually, that competition mixed with their location at the edge of civilization (China always had steady trade with the Middle East, and the Middle East was comfortable in the middle) led to the need for Columbus to sail. He went to 6 different kings with his crackpot theories before one accepted. China only had 1 head of state, who shut down travel to Africa. This was even though a hundred years before Columbus, 400 foot long, 28,000-crewed boats in massive treasure fleets sailed to Africa from China. But at about 1400, a new political group came to power in China that shut down international trade. They could have crossed to America, and might have eventually. But geography gave Columbus the incentive and societal carrots and sticks to travel first.

Or, at least, according to Jared Diamond.

A Review

When you spin a narrative like this, it’s easy to present conclusions as fact. You get to tell the information you want to tell. You weave your story, including only information that fits your theories, or misrepresenting information, or lying altogether. You can entrap people in story and the logic of the story will make your readers nod their head.

Stories shape our reality. The stories we tell ourselves and each other are meant to be internally consistent; if they weren’t, they wouldn’t be stories anymore. And those stories can often take a lot of outside information before they’re broken.

The extreme example; someone raised in a cult, told the outside world is full of monstrous people who want to tear her down and subject her to evil influences. But then she makes a run to the grocery store, or meets a neighbor, or watches TV, or whatever. Suddenly, she has to take in information that doesn’t match the story she’s been told. She can tell herself they’re lying. They’re just saying “Good morning!” to trick her, or presenting nice people on the show because they want to draw her in to the darkness. The alternative? She questions the story she’s been told. “Maybe people out there aren’t so bad,” she thinks to herself. “Maybe the story is wrong.”

Is this just “a story?” Is this just a story being told, that contradicts outside information but makes you nod your head while you’re inside of it?

Some experts would want us to think so.

Wikipedia, always a wonderful source of information, will show you dozens of scholars who disagree with major portions of Diamond’s work. This article at Inside Higher Ed summarizes the second round of arguments taking place in 2005 when the PBS series based on the book was created. This 2022 blog post also does a far bit to pick apart the criticisms of the book, especially the factual inaccuracies.

There are many who hate this book, perhaps most of all because it seems to let those descended from white Europeans to let themselves off the hook. “Those people in the past were just doing what people do, and by golly, those poor people in America and Africa got conquered cuz they were unlucky. So sad.”

In other words, people think the story this book proposes can reinforce other harmful stories people tell themselves, and that is dangerous.

However, I don’t think this is the case. Could a person use the story Diamond presents to validate their possibly harmful overview? Sure. A hardcore authoritarian Nazi could see in this story the rationale for their right to conquer other nations. “We have the luck of geography which leads to advancement, which we can share with other nations.” I kind of laugh to think about it, but that’s the exact rationale Sozin used to invade the other nations in Avatar: The Last Airbender. At the same time, a militant Communist could use this book to validate the story of oppression; the bourgeoisie in government (called “Kleptocrats” in this book) are there because they take advantage of the infrastructure of settled societies which we must overthrow.

In this case, it’s the same as before; you can absorb the information of this story into your story, or let it challenge your story. You can use the story in many different ways to serve your own.

I don’t think that’s Jared Diamond’s objective. His objective is to wrestle with human interaction in large swaths over time, human groups interacting with their environment and with their surrounding human groups. He’s attempted to take the facts as best as he can see them and create a framework to see the world.

I think he presents a pretty convincing argument.

While I can’t say one way or the other when it comes to the depths of individual cases or crops, I can say this about the book: I learned.

I learned history, geography, science, geology, biology, and much more. Even if his information is wrong or his conclusions incorrect, all the time you absorb incorrect information. It’s the nature of our modern world. Our job is to sift through it, to find what’s true and what’s not. Sometimes we take something to heart for awhile, making it a part of our story; then we find that something was wrong or unclear or only partially true.

But we adapt. We’re creatures created to take in information. We’re created to be molded by the things we experience and see and do and learn.

So while ultimately, there are portions, perhaps even large portions, of this story that are wrong, this is just another springboard. Everything we learn catapults us into the next thing we’re going to learn and experience. Maybe I’ll find Diamond was wrong someday; but for now, it fits the story as I see it. Maybe I’ll learn something to contradict it, in which case I will continue to adjust my story.

But either way, I adapt to my circumstances. We all do.

And that, according to Jared Diamond, makes us uniquely human.

𝙷𝚒! 𝙼𝚢 𝚗𝚊𝚖𝚎 𝚒𝚜 𝙽𝚊𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚗. 𝙸’𝚖 𝚊 𝚐𝚛𝚊𝚍𝚞𝚊𝚝𝚎 𝚜𝚝𝚞𝚍𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝚠𝚑𝚘 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢𝚝𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚕𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚛𝚎𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚘 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚝𝚊𝚕𝚔 𝚊𝚋𝚘𝚞𝚝 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚖 (𝚜𝚘𝚖𝚎 𝚠𝚘𝚞𝚕𝚍 𝚜𝚊𝚢 𝚝𝚘𝚘 𝚖𝚞𝚌𝚑!) 𝙵𝚘𝚕𝚕𝚘𝚠 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚋𝚕𝚘𝚐 𝚝𝚘 𝚜𝚎𝚎 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚎𝚗𝚝!

Leave a comment