Civil War is a 2024 dystopian thriller film by writer-director Alex Garland from A24, the independent entertainment production company behind 2022’s smash hit and critical success Everything Everywhere All at Once.

I’m not one to comment on politics, especially publicly. My views are constantly shifting, and I’m always taking in new information on local, state, national, and global situations.

I went to go see Civil War with my wife two nights ago after not even knowing it existed until last Tuesday. The studio did an amazing job marketing it last week, putting out ads all over Facebook, YouTube, and Roku. I was pulled in from the beginning.

It is worth a watch if you’re into arthouse films, war movies, thrillers, contemporary politics, and psychology. However, it’s different than you might expect. It’s a unique movie, thoughtful, with strengths and weaknesses. It’s not Alex Garland’s best (that’s still his 2014 directorial debut Ex Machina) but it is a powerful movie that is worth a watch.

If you’re interested at all, don’t read my review. Go and watch it; I’m going to spoil major portions of it, but not all of it. Read on for analysis and opinion.

An Interesting Movie

This movie isn’t quite what I thought it would be.

The marketing pitches the movie as an examination of contemporary American politics. Of course, marketing never exactly mimics the movie. The title, Civil War, might seem like it too.

However, the movie isn’t quite like that.

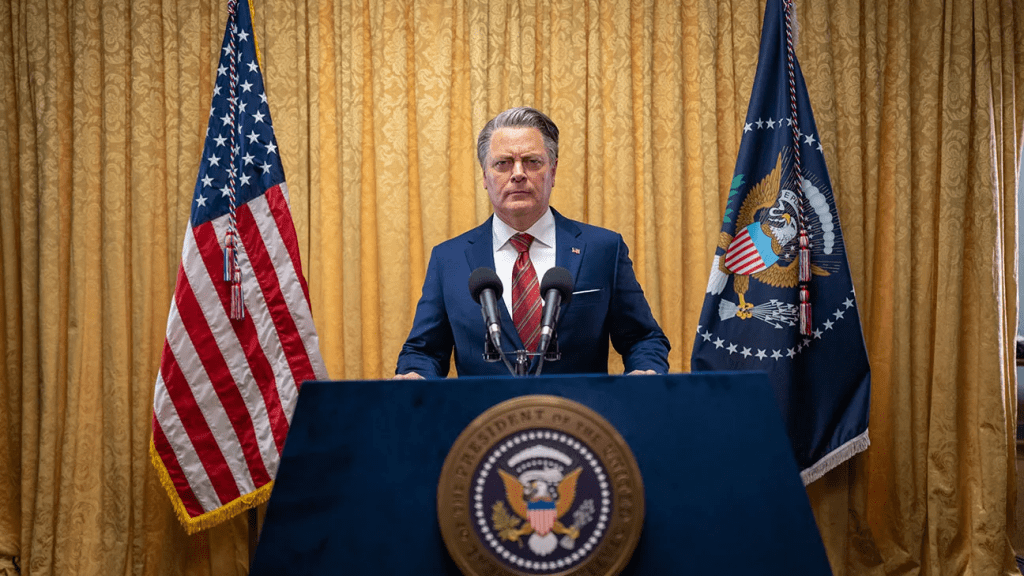

The movie doesn’t really go into detail on the political situation. It’s in the near future – the New York City skyline features 3-4 added buildings that are taller and more “sci-fi” than the One World Trade center or other buildings. There’s a president who somehow won a third term, who dismantled the FBI and some other Government departments. He’s bombing civilians. He’s clearly the bad guy.

But somehow, the Western Forces, the secessionists, are a team of California and Texas. There’s another secession of the north-west from Oregon to Minnesota. Florida has seceded too. You pick up on a lot of this from maps in the background, subtext in dialogue, and graffiti on walls. The war has gone on for 14 months and food and water is running out. Many people are just living their lives and trying to ignore the situation.

We’re not sure who the leaders of the factions are besides the President. We’re not sure what party he was from – he both quotes that God will help him, and that he dismantled law enforcement. We don’t know if the rebellion was reacting to his regime, or his regime was reacting to them. We’re not really sure who we’re following; at various times, we’re with Western Forces soldiers or Military soldiers, but it’s explained visually. We know the Western Forces are in Charlottesville and are almost at Washington, D.C.

We’re following a team of war reporters and their tag-along protégé who have been across the world, never thinking this would come at home. People party and deal with the pain in their own ways.

The point isn’t really this hypothetical war that’s a reflection of modern American politics. It’s not trying to see what would happen if our country, right now, had a civil war – a problem much debated in modern political discourse. Instead, it’s more a study of what happens when civil war happens.

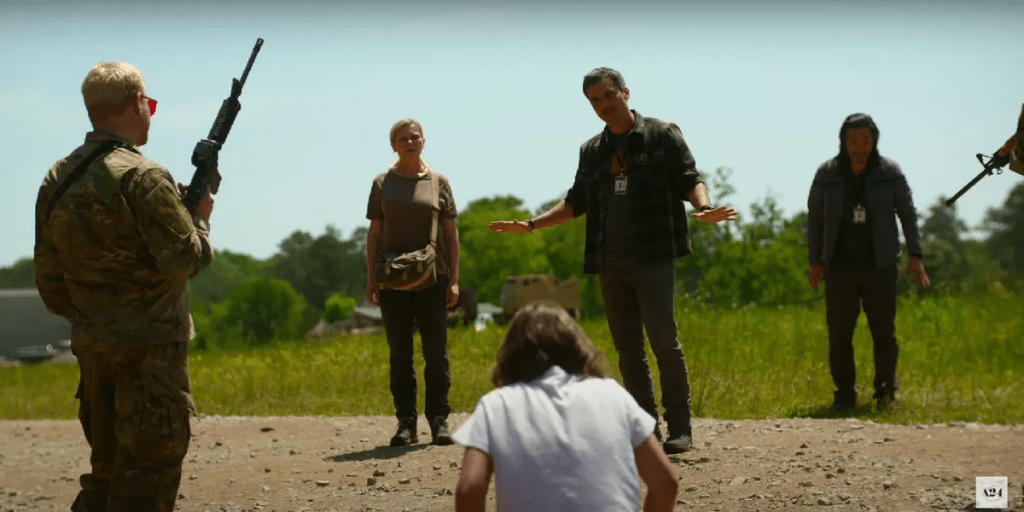

It’s a travelogue movie. We go from situation to situation, place to place. Each puts Western Forces, military, average people, looters, and of course the reporters in different situations. We get to see how tons of different people react to a situation like this one. They’re put into psychologically demanding, frightening scenarios. A US military soldier pulls the group over. They stumble on a gas station where a small group protects their gas from looters. They come into a battle where one of the reporters tags along, chatting with the soldiers. In each situation, we see how people react. How would you react? What would you do? What would you feel?

It’s less a war movie following battles in a conflict, and more of a thriller movie examining how people act in domestic upheaval. It’s not trying to be about how our current country became embroiled in a civil war, but more how the people of a country like ours reacts to a civil war.

If you go in expecting a war movie or a political commentary, you’ll probably be disappointed.

If you go in expecting a psychological thriller, you’ll be surprised and wowed.

War Correspondents

Along with that, it’s an examination of the nature of reporting, photography, and war correspondents in particular.

Lee Smith, played by celebrated American actress Kirsten Dunst, is the main character, an experienced war correspondent who is feeling the wear and tear of trying to keep war away from home and yet it happened anyways.

Along with her is Joel, played by Brazilian Narcos-veteran Wagner Moura. He is a journalist. He’s a talker who is able to weave his way into people’s good side and get answers out of them. There’s also Sammy, played by Stephen McKinley Henderson, who’s an elderly journalist who sees this as his last hoorah. Tagging along is Jessie, who Lee met during a suicide bombing and who wishes to be a war photographer as well.

Lee and Jessie have the most prominent arcs. Lee goes from uncaring and cold, worrying if this has all been in vain, to protector of Jessie. Jessie goes from terrified and shaking to confident and competent. Their arcs are easy to see, sometimes too much so – I wish it beat you less over the head and spent more time filling out the empty spaces in their stories. Sammy has an arc too, but it’s not much more than the old man trying one last time to make an impact on the world. The impact he creates will surprise and shock you.

Joel, however, was a standout for me. While Lee and Jessie are more obviously characterized, Joel is much more subtle. He’s a talker, often taking the front lines when they’re talking or debating. He can talk up Lee or talk down Jessie. He asks questions, getting answers as to how all of these people are reacting to the civil war tearing through this alternate version of the United States. However, he gets himself into a situation he can’t talk himself out of, and it tears him apart, hardening him while Lee begins to soften. In the end, words fail him when he tries to comfort Lee. He gets his dream, but it is disappointing. Was it worth the cost? Rather than beating you over the head with this, though, you have to pick up on it in his interactions and conversations. His character is well filled-out even if we know less information on him than Lee and Jessie.

Too Much Art?

You’ve noticed something by now: this film’s greatest strength and greatest weakness is its visual storytelling.

You have to infer context from visuals. You have to figure out an arc by situation and action, or lack thereof, instead of just being told who this person is and who he’s becoming. Your eyes bounce back and forth over shocking war visuals beautifully captured – often literally – on camera.

However, there are also gratuitous shots, where the “wow”-factor was thought of more than the “What-is-this-saying” factor. The crew drives through a burning forest while a passenger dies. It’s beautiful. It’s cool. It looks mostly practical besides a few shots. But what is it saying? Is the character’s life burning away? I don’t think we need 2 minutes of burning shots for that to be communicated. And this character should be receiving first aid, and support, and instead they’re just leaving them to die in the seat. Where’s the first aid? Why isn’t so-and-so sitting next to him holding his wound, bandaging him? How do they NOT have first aid if they’re war correspondents wandering through dangerous situations?

There are a lot of interesting shots – driving through suburban neighborhoods with helicopters crashed into roofs. Bodies hanging from an interstate overpass. Tracers lighting up the sky in the distance while the crew watches. Helicopters hovering through an urban war zone, firing at all it sees. However, while they are thoughtful juxtapositions, often that’s just what they are. For a movie meditating on the concept of “how people react in horrible situations,” we don’t see people reacting to these horrible situations. You’re left to react. The helicopter in the roof is for your thoughtfulness, rather than the character’s. Depth could be gained, even from seeing Jessie cringe at the caved-in roof, from seeing Joel shake his head at the body by the overpass. Artsy shots are great and all in a movie about people who take thoughtfully artsy shots. But artsy shots one after another don’t necessarily make a strong story.

A story is an interconnected series of events driven by characters. The less connections between the events beyond “This is for your consideration, audience,” the more the movie becomes a powerpoint slide of horrible war images rather than a thoughtful study of people reacting in horror.

That’s not to say that there isn’t story, There is. I wonder if on a rewatch I’d notice more of those subtle reactions, more of those lines that have much more subtext than at first glance, more shots that are reacting to statements or ideas or arcs of these characters. But at first watch, I see a compelling story mixed with artfully moving images. I wish I saw a tightly written, compelling story told with artfully moving images.

Conclusion

Watch Civl War. While it’s not a war movie, or a political opinion piece, it is a thoughtful examination of what people do in intense situations and what war correspondents do in domestic and personal conflict. It often has stunning visuals and more-than-meets-the-eye storytelling, but I think it could have been improved and tightened even more.

As it is, it seems it’s left a lot of reviewers wanting. It’s not political enough, not war enough, not deep enough. It’s thoughtful, but not thoughtful enough.

Maybe. Maybe not. But I think either way you’ll be moved by this engaging thriller where you see humans – and Americans – at our best, and at our worst.

𝙷𝚒! 𝙼𝚢 𝚗𝚊𝚖𝚎 𝚒𝚜 𝙽𝚊𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚗. 𝙸’𝚖 𝚊 𝚐𝚛𝚊𝚍𝚞𝚊𝚝𝚎 𝚜𝚝𝚞𝚍𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝚠𝚑𝚘 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢𝚝𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚕𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚛𝚎𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚘 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚝𝚊𝚕𝚔 𝚊𝚋𝚘𝚞𝚝 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚖 (𝚜𝚘𝚖𝚎 𝚠𝚘𝚞𝚕𝚍 𝚜𝚊𝚢 𝚝𝚘𝚘 𝚖𝚞𝚌𝚑!) 𝙵𝚘𝚕𝚕𝚘𝚠 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚋𝚕𝚘𝚐 𝚝𝚘 𝚜𝚎𝚎 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚎𝚗𝚝!

Leave a comment